- 1

-

We define a

strwhich we will use as our file name. The extension (the part after the.) is optional. Its only purpose is so that Windows/Mac knows which program to open the file with when you double-click it.

- 2

-

We use the

open()function by passing in the name of the file and the ‘mode’ we wish to use. In this case the mode is'w'which stands for “write”. Theopen()function returns a “file handle” which we store inf. - 3

-

We can access a variety of methods attached to the file. The full list of methods is given in Table G.1, but a partial list is given below. In this case we use

write()to write the given text. - 4

- It is necessary to close a file when done, otherwise it cannot be opened by other programs. Files generally need to be “locked” when in use so that multiple programs can’t write to it at the same time.

6 Files and IO

Table of contents

Upon completion of this lesson you should:

- …appreciate the 2 main types of memory in a computer

- …be familiar with the file system, files, and folders

- …understand both relative and absolute file paths

- …know how to write simple text to a file, and read it back in

- …be able to format text to create desired output in files

- …be able to use the command line to perform basic tasks directly

- …know how to install external python libraries using the command line

6.1 Types of Memory

We have not talked much about how computers work internally. As we write more complicated computer programs we need to understand more about how the computer deals with data because it impacts performance. Examples of this trend are advanced numerical algorithms such as machine learning or climate modeling.

It is convenient to think of computer memory as being either permanent and slow or temporary and fast.

6.1.1 Permanent Memory

There are many types of permanent storage, but the most common type uses a “disk”, sometimes called a drive. Disks can be removed, but all computers have at least one internal disk which cannot be removed without breaking the computer. Several types of removable disk are shown in Figure 6.2.

Data is stored on such a disk as follows:

- Data on a computer is internally represented in binary numbers (1’s and 0’s).

- Computers use binary numbers because it is easy to signify 2 values using high/low voltage, high/low resistance, high/low magnetism, etc.

- Writing binary values to a disk is then done by applying some high/low signal to the disk.

- For example, in the case of magnetic storage the values are created using a magnetic field to impart magnetism to the disk.

- In the case of a CD, DVD, or BlueRay disk, the values are holes in a metal film on surface. In all cases, the disk holds these values as long as it’s not damaged or decayed by time.

- For example, in the case of magnetic storage the values are created using a magnetic field to impart magnetism to the disk.

- Reading values from a disk is done by scanning over the disk surface and detecting the high/low values which were created during the writing process.

- In the case of a magnetized disk the needle is a magnet that is attracted or repelled by the magnetic value on the disk.

- In the case of a CD/DVD/BlueRay, a laser scans the disk and detects the reflection or lack thereof due to the holes.

- In the case of a magnetized disk the needle is a magnet that is attracted or repelled by the magnetic value on the disk.

By understanding a little bit about the disk reading/writing process, we can appreciate that it is a physical activity that requires moving parts and mechanical processes. Knowing this, we should not be surprised that reading and writing to a disk is a slow process. Therefore, if we are trying to write a fast program, we should avoid reading/writing to disk when possible.

Github has taken long-term storage to a new level.

6.1.2 Temporary Memory

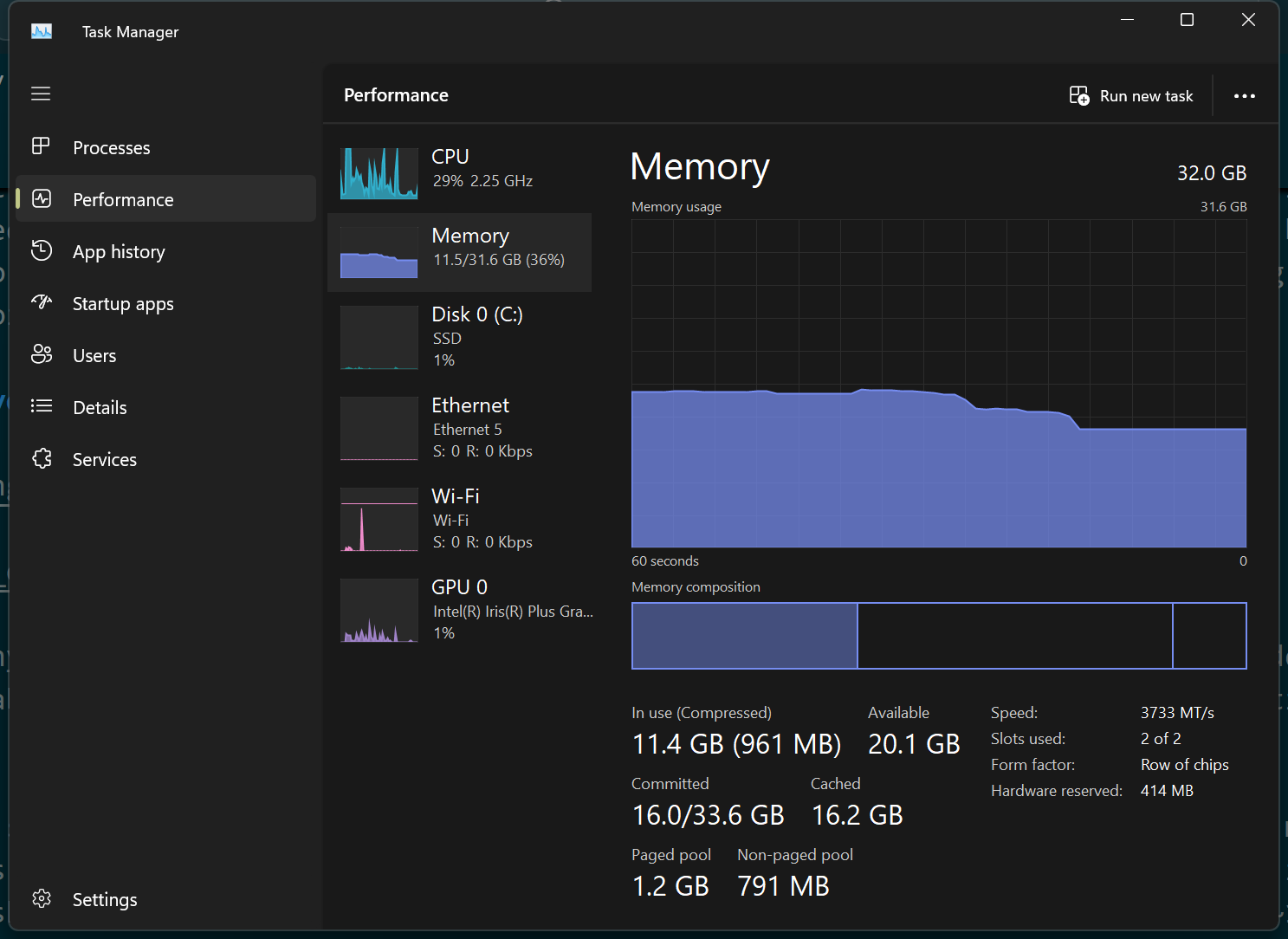

Computers also have a second type of memory, usually called RAM (Random Access Memory). RAM is much like ‘short term’ memory in humans. It is where we keep information which we are actively working on. RAM is designed to be much faster than a disk, but normally there is much less of it. A typical computer might have ~10 GB of RAM, while having ~1000 GB of disk space.

We typically use RAM as follows:

- When we open a file, the PC retrieves it from the disk which can take an annoyingly long time

- The data from the file is then loaded into RAM where we can read and write it as needed with much less speed penalty

- Once we are finished with the data (i.e. file), we save it and close it. The computer then writes the updated data to the disk and purges the data from the RAM.

The RAM can become overfilled if we open too many large files. In this case the operating system will begin writing data to the disk. If you computer ever becomes noticeable and frustratingly slow, it is probably because this is happening.

The sum it all up, think of a information stored on disk as long-term, semi-permanent storage; while anything that the computer is currently working with is moved into active memory.

6.2 Files and Folders

When reading and writing data to the disk, the computer’s “operating system” (i.e. Windows, Mac, Ubuntu, etc.) presents us with a very familiar interface for dealing with stored data: files and folders.

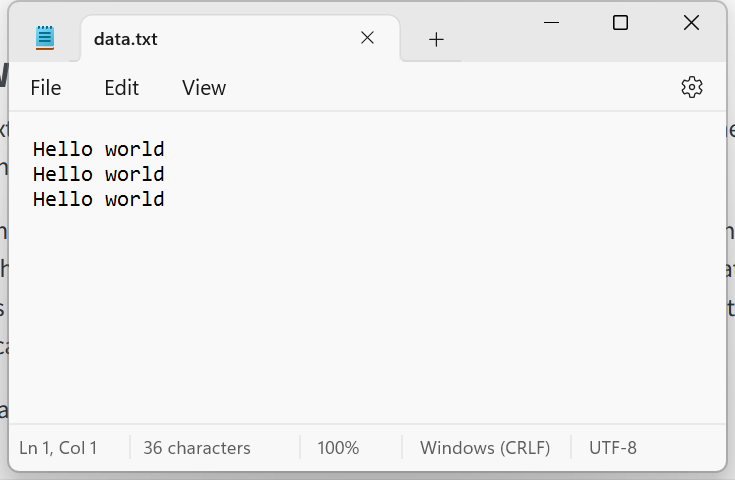

One extremely frustrating feature of Windows is that the file extension is hidden by default, so the files appear as “my_resume” instead of “my_resume.docx”. Enabling this visibility is a very good idea. This tutorial shows the process for several different versions Windows.

- Data is stored in files.

- Common examples are are Word documents and images. We might have a Word document on our computer like

my_resume.docx, or a picture likefriends_at_pub.png. - The part after the last dot (

.) is called the file extension. - The only purpose of file extensions is so the computer (and the user) know what program to use to open the file. If the extension was removed, you could still open it if you used the correct program.

- For example, Outlook will not let you send a

.pyfile because it could contain malicious code which the recipient might run. However, you can sendcode.py.temporcode.txtand Outlook will let it through. Then the recipient can change the extension back to.py.

- Common examples are are Word documents and images. We might have a Word document on our computer like

- Files are stored in folders.

- Common examples are your “downloads” or “documents” folder.

- Folders can contain many files

- Like real folders, folders can be stored inside other folders like

/pictures/2020/January/PartyInNYC.

- Finally, folders are stored on a disk.

- This is where the analogy to real world file systems breaks down because disks should be called “cabinets”.

- A disk is a physical device inside the computer where data can be written. This is usually described as “storage”.

- On Windows every disk is given a letter, with

C:\usually being the “main” drive. - On Mac the disk are not given letters, and they kinda all act like they are a folder themselves

- If we combine all of these together we get a path.

- On Windows the path looks like:

C:\users\jeff\photos\ufo_sightings\591.jpg- And on Mac it looks like:

/Home/jeff/photos/bigfoot_sightings/431.jpgThe above paths are considered absolute paths since they contain the entire path, from the disk letter all the way to the file. It is also possible to have relative paths which contain the part of the path below the current directory. For instance, if we are currently in C:\users\jeff, then photos\ufo_sightings\591.jpg is a relative path to the file.

Note that Windows and Mac use different direction slashes. Recall the discussion about the use of escape characters when backslashes needed to be written (\\). This is particularly annoying on Windows since \ is used in the paths, while on Mac the / can be used without any escaping.

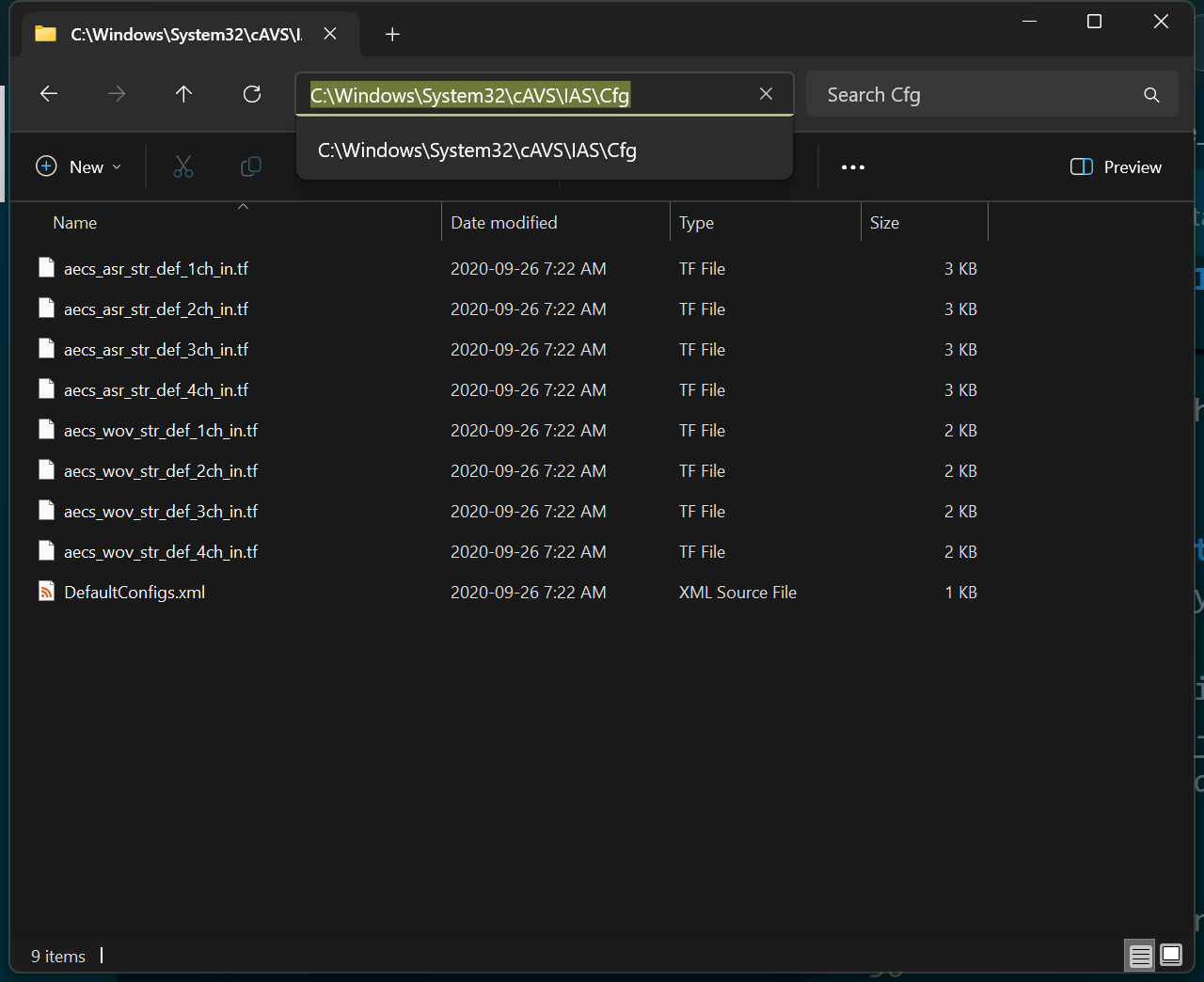

Below is a screenshot of a random folder deep within the Windows directory. Also shown is how title bar reports the absolute file path if you click it.

The point of storing files inside a hierarchical folder structure is for organization. Consider the file storage room in shown in Figure 6.5. If you are given a location (i.e. a path) in the form of aisle 8, section 4, shelf 4, box 11, page 10, line 55 you could find the exact sentence in a text file! The file system on a computer works exactly like this.

6.2.1 Finder/Explorer vs Command Line

Now that we understand how our computer stores our data in the form of files, we can appreciate what is happening when we browse our files using the Explorer in Windows (or Finder on Mac).

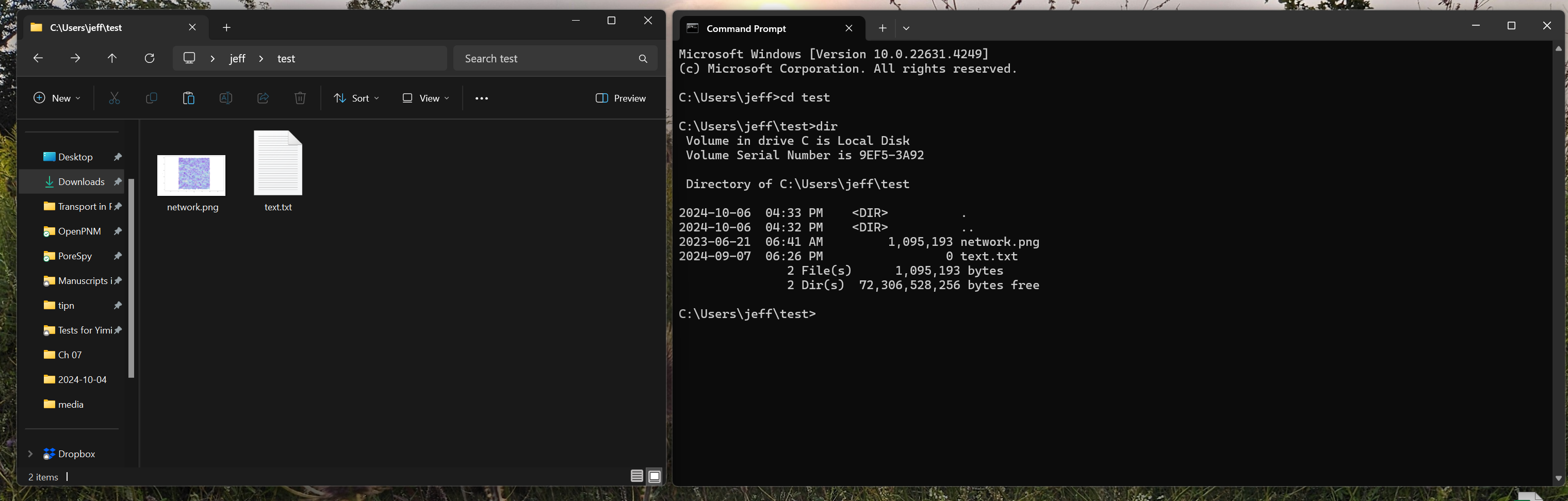

However, there is an alternative way to navigate our files: using the command line. Consider the following comparison:

A major milestone on the path to becoming a proficient programmer is learning to use the command prompt (sometimes known as the command line or terminal). Modern operating systems provide gorgeous and powerful graphical user interfaces (GUIs), but ultimately our button clicks and checkboxes get translated into commands to be run by the computer. The command prompt lets us call such commands directly, bypassing the GUI. There are 2 main scenarios where we may need to do this:

- As “power-users”, we often need to interact with the computer more directly than the GUI allows. The GUI hides many features and options since the vast majority of computer users do not need them.

- There are many essential utility applications which do not have a GUI so must be activated from the command prompt.

The following table illustrates an example of working from the command prompt to open a text editor, in both Windows and Mac.

| Windows | Mac |

|---|---|

Press Windows key to open Start Menu |

Type cmd+space to open Finder |

Type cmd and press enter |

Type terminal and press enter |

At the “prompt” (C:\) type notepad |

At the “prompt” type open -a TextEdit |

| When you press enter, the NotePad application will open up | When you press enter, the TextEdit app should open up |

| This is exactly equivalent to opening the start menu, typing “notepad” and clicking on the icon that appears. | This is exactly equivalent to opening Finder, typing “TextEdit” and pressing enter. |

The number of commands that are available is enormous, and each one has different options. The following links provide “cheat sheets” for the most common and useful ones, to give a flavor of what is possible:

There are a few commands that are so common and useful that they are worth highlighting:

| Listing contents of current directory | In Windows the command is dir, while in Mac it is ls. |

| Changing current directory | It is cd is both Windows and Mac. cd.. moves up one level, cd <folder> moves down to specified folder. |

6.3 Reading and Writing Text to a File

6.3.1 Writing to a File

Writing text to a file is one of the ways we can make our data “permanent”, otherwise all of our calculations are lost when we shutdown our computer.

Because this is such an important task, Python has a built-in function for working with a file: open(). The open() command does not “open” a file physically for us to look at, they way Word does when we double-click a file name. Instead Python “opens” the door to the file so that data can flow in and out.

The general syntax is as follows:

If you create a file solely using a file name (i.e. no directory information), then the file will be created in Python’s “current working directory”. Luckily this is pretty easy to find:

- 1

-

The

osmodule has lots of functions for navigating your file system, as well as general information like the number of cores available, etc. - 2

-

Here

cwdstands for “current working directory”

This will return something like C:\Users\jeff\projects. If you navigate to this directory in your explorer/finder you will see your file (i.e. 'data.txt')

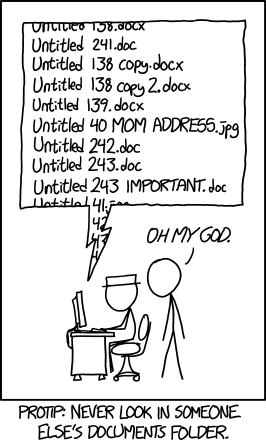

The result of writing “Hello world” to this file is shown in Figure 6.8 on the left:

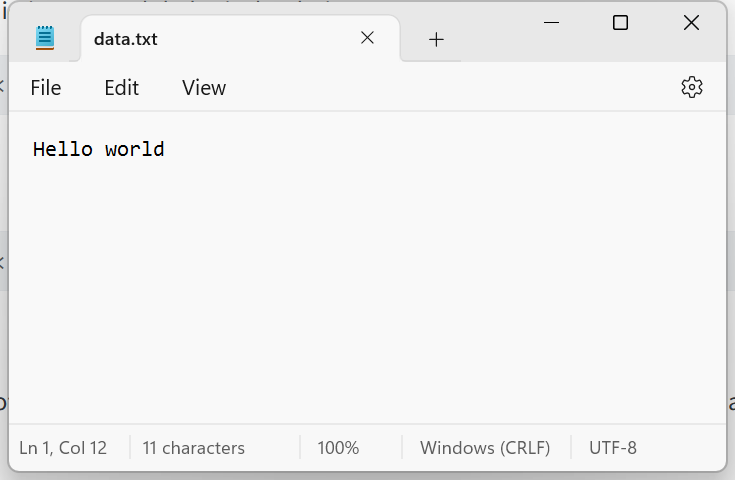

If we write to the file 3 times it will append the text to the existing text, creating one long line as shown in Figure 6.8 (middle)

fname = 'data.txt'

f = open(file=fname, mode='w')

f.write('Hello world')

f.write('Hello world')

f.write('Hello world')

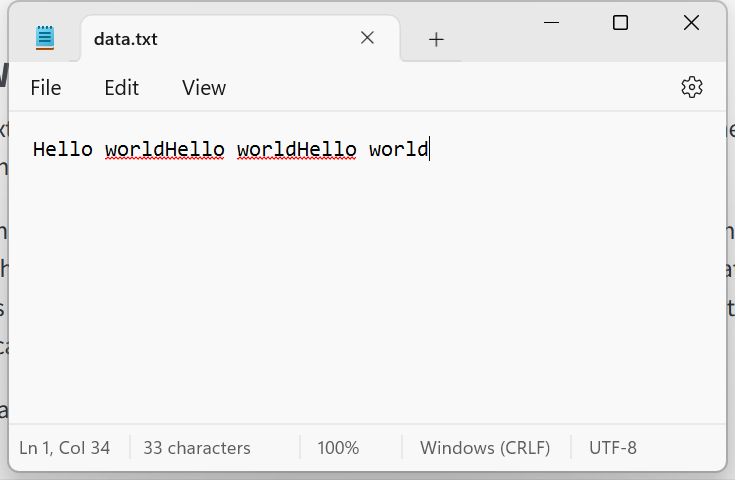

f.close()And finally, using our knowledge of escape characters from last chapter we can add a new line after each write to get the result in Figure 6.8 (right)

fname = 'data.txt'

f = open(file=fname, mode='w')

f.write('Hello world\n')

f.write('Hello world\n')

f.write('Hello world\n')

f.close()Here is a good time to reveal how I know about all these hidden features buried under so many levels of abstraction:

I Google it!

I use a search term like “how to find the current time in python using standard library”. I usually look for the StackOverFlow links. Here is the page on StackOverflow. There are many answers, each proposing a different way to do it, complete with commentary by other coders and an upvote/downvote count to indicate how valuable the other users (like us!) found the answer.

6.3.2 Reading From a File

Reading data from a file not only let’s us reload data we may have written to a file, but it is also common to store tabulated data like constants and fitting parameters in files.

Let’s start with something simple to see how it works:

- 1

- First we will open a new file and write “Hello world” in it to ensure the file is present.

- 2

-

Here we open the file in “read” mode (

'r'). - 3

-

The

read()function reads the entire contents of the file in tocontentswhich we then print to see it contains'Hello world'

Result: Hello world6.4 Installing External Packages

We have already dabble in this briefly when installing streamlit to run the grader apps, but let’s take a closer look.

We have already seen that Python includes many additional packages as part of the “standard library”. These provide functionality that is often important, but not necessary for everyone. The programmer can therefore import the extra functionality when needed.

Although Python’s standard library is considered very good (compared to most languages), it cannot possibly consider everything. For this reason we can install “external packages” from a variety of sources. The most common source is The Python Package Index or PyPI.

Installing packages happens to be one of the reasons why a competent programmer should be comfortable using the command line. We usually install packages by opening the operating system’s command prompt and typing pip install <package-name>. However, it is not quite that simple because it depends on how Python was installed.

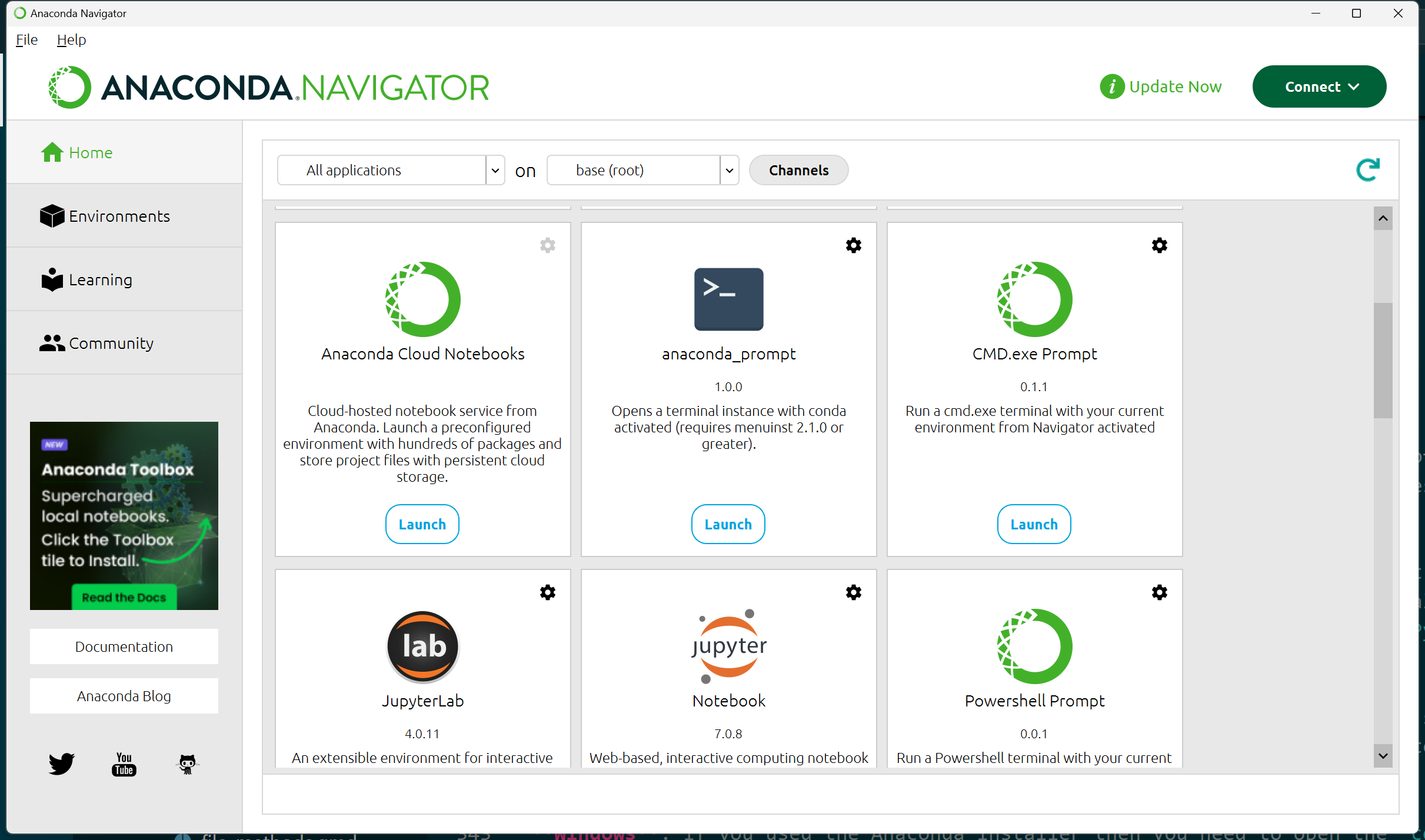

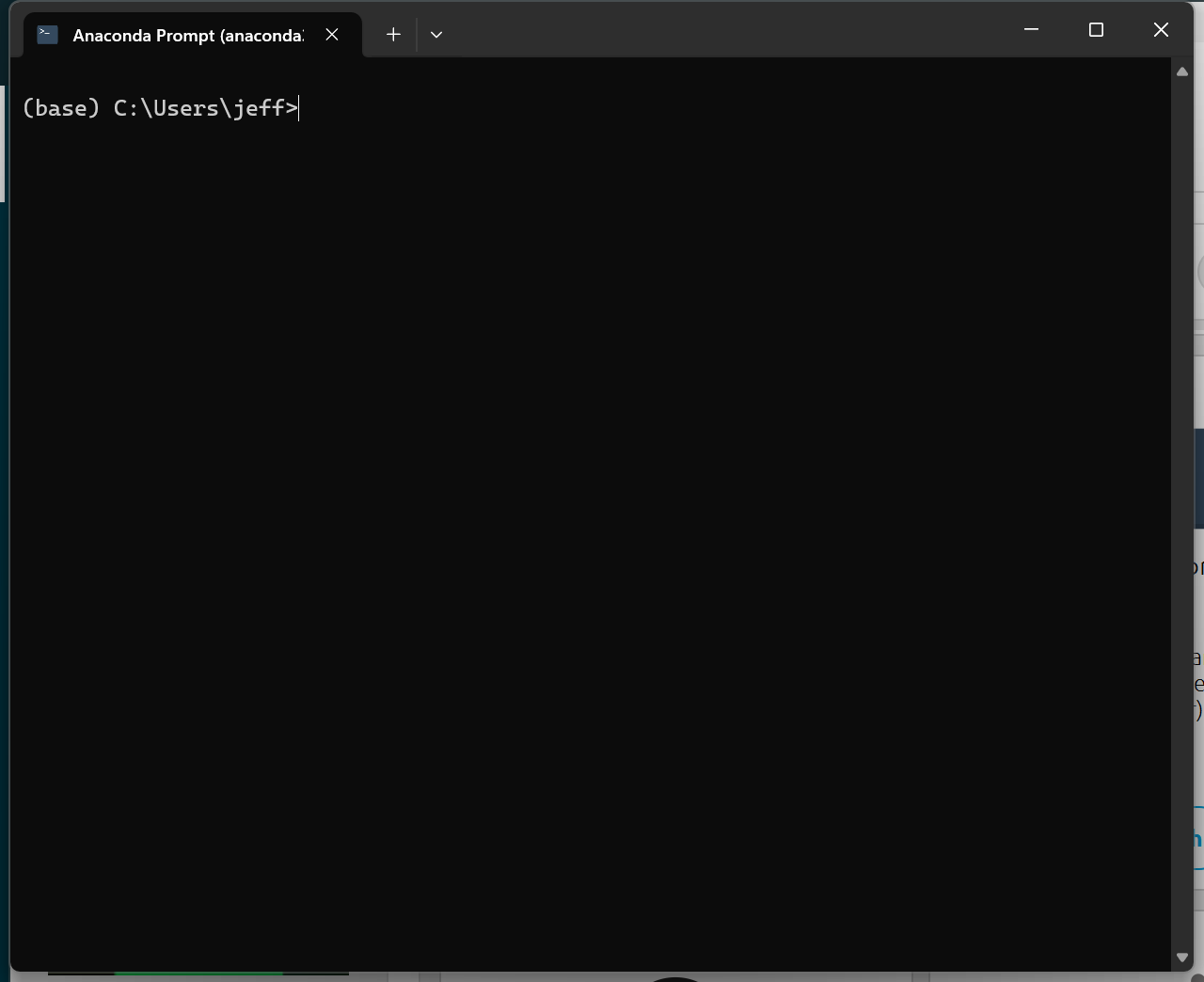

For our purposes, we can avoid complications by using the anaconda_prompt via the Anaconda Navigator.

This “prompt” has special capabilities, including the ability to use pip without any additional setup. Test that pip is available and working by typing:

(base) C:\> pip listThis will give you a list of all packages that are currently installed. What this line does is the following:

- Runs a program on your computer called

pip - Every other item on the line gets passed to

pipas an argument, in much the same way arguments are passed to functions.

pipwill run using the arguments you passed, and do something. In this case is prints a list of all installed packages.

Now that we have the ability to to install and use more complicated packages, we can revisit some tasks and do them differently.